The Hex:

The Hex: A Curse on Obvious Allusions

The Hex: Walk to A Meta Universe

The Hex reaches a culmination with the fifth character, Lazarus Bleeze, a space marine. A knock at the door sends him into hiding. Irving has arrived to arrest him. A puzzle leads Lazarus into his game; a top down game where Irving shoots hordes of aliens, like Starship Troopers. Lazarus works with three other members of a squad to defeat the aliens. As the mission seems to wrap up, The Hex reveals the deception. The aliens are the fake Moogles and fake Goombas from Legendaria and Weasel Kid respectively. Lazarus' squad is infiltrating Gameworks to recover a relic and free Sado. Weasel Kid has broken into the sewers underneath Gameworks to bomb the foundations. The explosion from the bomb “breaks” The Hex.

In the chaos, Lazarus confronts Sado over the relic. Transforming into a gigantic spider, she forces him into mini-games with symbols like a Ring, Pokeball, Tetris block, and a frying pan (PUBG).

Then one of the characters murders one of the other characters. The barkeeper makes a pathetic Clue reference, as he speaks directly to the player. Breaking the fourth wall, he asks if the player is satisfied, and the player can choose Yes or No. Choosing No transfers the player to the Question Mark character (I don't know what Yes does). The barkeep tells Question Mark to visit a cabin outside the inn. After another puzzle, the player enters a commentary by Lionel S (reminiscent of The Beginners Guide). Lionel developed each of the games. In the game called Walk, the player listens as Lionel describes his life story. How he started as an idealistic developer who broke into the scene with the success of Super Weasel Kid. How he sold out and made Combat Arena. How Sado came to exist. How he made more money than he could spend. How he made Legendaria, but a subordinate sabotaged it. How it bombed, he lost his money, so he stole from the company and fled the country. In exile he made Rust and hated it. He hated the modders even more. So he sued them.

Lionel is an egotistical and an unreliable narrator, trusting no one but himself. His thoughts lack insight, only describing the tangible layer of experience. He is so wrapped up in himself, that the player can see many of his statements as outright lies.

As Walk ends, the cloaked creature reappears. He explains how the player can escape this driveling commentary.

At the finale the player sneaks back to a glitched exit. The player enters a new game featuring the barkeep as a server of root beer. The hooded figure is there as well, sweeping the floors. Goombas and Moogles show up for root beer.

After the root beer game, the characters gather to activate the relic, a golden hex. With the player's help, they reach through into reality and strangle their maker, Lionel.

A scene after the credits reveals Sado in the real world behind Lionel's dead body.

The player can return to the game and play any of the mini-games to unlock additional secrets.

The Hex uses a familiar sequence. With each new character the player has;

A puzzle in the inn.

A time in their game which parodies one or two real life games. The game always goes downhill over time, and most of the time the character wants to escape.

They meet the robbed figure, meet other characters from the bar, meet Irving, and hear about Lionel and Gameworks.

Go back to the bar.

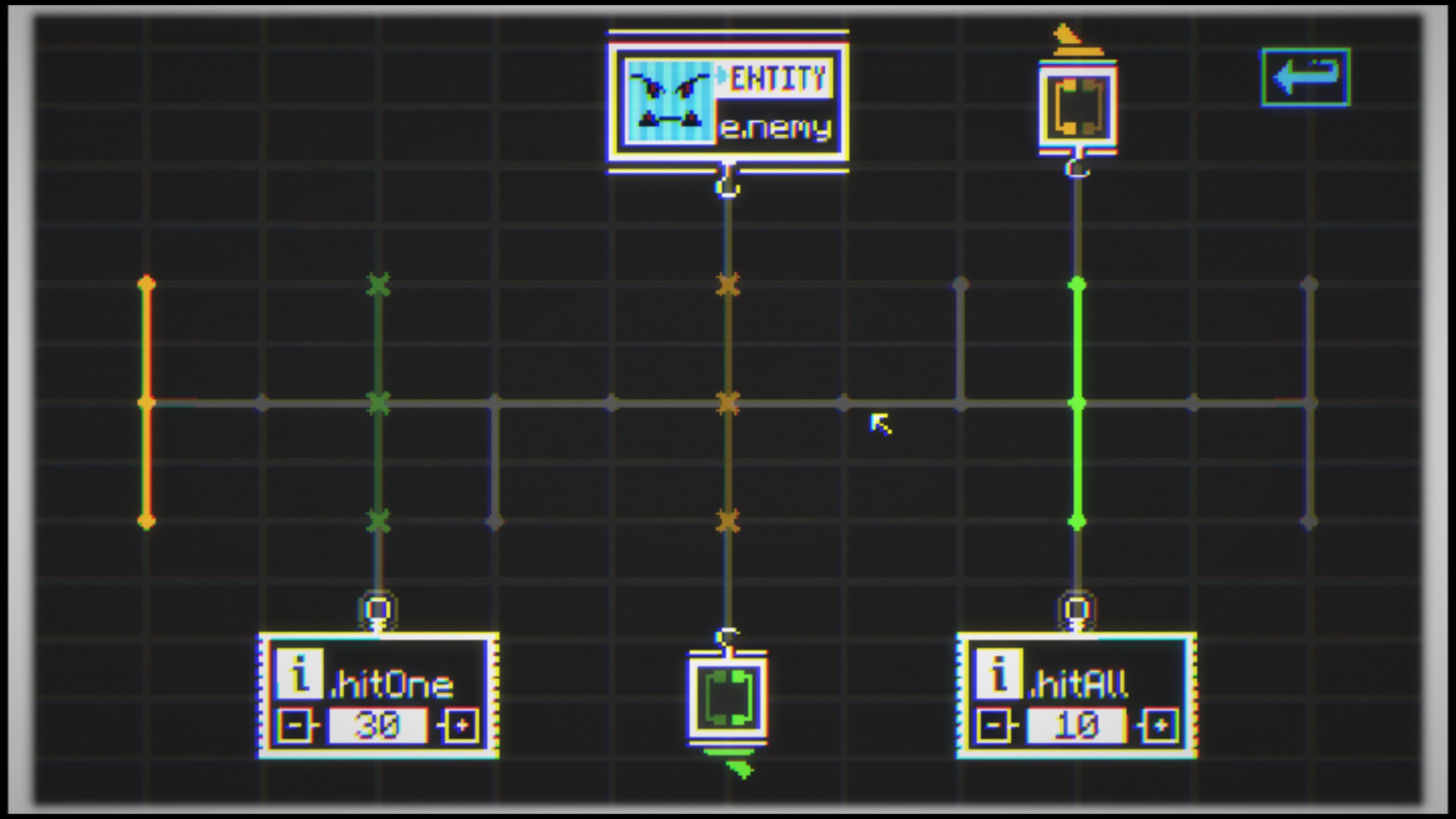

This cycle ensures that The Hex has dozens of different mini-games and mechanics, because most characters encounter two or three each. They are all different, but they are all very easy and simple. Some might not even think of them as games, but as tedious chores to progress the story. Their lack of complexity makes it easy to keep moving forward. It's almost impossible to fail, but this also renders them abysmal. Not a single game is better than the game it parodies. The player is forced to play through dreadfully dull platforming, shooting, puzzles, and RPGs.

Obviously the developer knows this. He wants to use these mini-games as a vehicle for the story. The premise, as eventually revealed to the player is, what if the video game characters created by a developer are alive? They feel used by their creator and seek vengeance. But Mullins seems too invested in deploying a host of pointless references. He alludes tropes and breaks those tropes. He reels off clear parodies of other games, while satirizing them.

Is this clever, or an unpleasant attempt at appearing clever? Is the author intelligent, or trying too hard to appear so?

In Conclusion,

The Hex employs a deceptive opening, misleading the player about the plot and therefore the gameplay. Instead of trying to discover the murderer the player controls a series of parodies of video game characters, playing tiresomely simple mini-games.

The developer deploys tropes and obvious parodies, with the intent to break every one. The Hex isn't as much a game, as watching a movie made by a person who thinks they are smart, deploying incoherent references and slipshod satire. They are as subtle as being hit by the Hammer in Super Smash Bros. If you want to watch someone show off how smart they think they are, The Hex may be for you.

The game is packaged in a visual and audio quality that isn't average; its grating, especially the electronically chipper mumbling of the characters. It's reminiscent of Banjo-Kazooie's character speak, but outdated and less charming. The only possible defense for this design; the poor visual and audio design are an intentional decision to subvert expectations and industry practice.

The element of Daniel Mullins games that seems to draw fans, aside from the appearance of intelligence connected with recognizing and breaking tropes, is the multitude of hidden content. There's tons of mini-secrets in the game, in the game code, and connected across all three of Mullins' games. The enjoyment of secrets seems akin to the obsession with FNAF lore.

To outsiders, or those who don't get it, it seems shallow, but maybe to those who enjoy it, it is no different than the interconnected stories told by Robert Heinlein, J.R.R. Tolkien, or Thomas Hardy.

Unfortunately, I just don't get The Hex.

Comments

Post a Comment